Achieve flare-free operations using fit-for-purpose technologies and techniques

The Defining Series: Oil and Gas Exploration Essentials

Published: 09/09/2015

The Defining Series: Oil and Gas Exploration Essentials

Published: 09/09/2015

The earliest users of petroleum did not have to search for it. Most likely they stepped in gooey tar and it stuck to their feet. These first encounters with petroleum were at seeps, where oil and gas, which are less dense than water, rise from subsurface rock formations to the Earth's surface. Over time, people found practical applications for petroleum, such as weaponry, waterproofing, lighting and medicine.

When surface supplies became scarce, people dug into the ground near the seeps to find more, just as they dug wells near springs to find water. Eventually hands, picks and shovels gave way to drilling methods that today can access much deeper resources.

Over the years, petroleum geologists learned to look for hydrocarbons not only where they had been found before, but also where conditions were similar to those of earlier discoveries. For example, they noticed that oil and gas were sometimes found in anticlines, where rock formations that were once flat had been folded into an arched structure. Geophysical techniques, such as seismic surveys, were developed to help detect such structures in the subsurface. However, not all anticlines contain hydrocarbons, and hydrocarbons can accumulate in other structures.

To organize their knowledge about the occurrence of oil and gas discoveries, explorationists defined the petroleum system as the geologic elements and processes that are essential for the existence of a petroleum accumulation.

- Trap—a barrier to the upward movement of oil or gas

- Reservoir—porous and permeable rock to receive the hydrocarbons

- Charge—including

- Source rock—a rock formation containing organic matter

- Generation—temperature and pressure conditions to convert the organic matter into hydrocarbon fluids

- Migration—buoyancy conditions and pathways for the fluids to move from the source rock into the reservoir

- Seal—an impermeable cap to keep the fluids in the reservoir

- Preservation—conditions that maintain the nature of the hydrocarbons.

When these elements and processes occur in the proper order, chances are good that a petroleum accumulation exists (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Requirements for a petroleum accumulation. Sediment deposition in the past (top) may lead to hydrocarbon discoveries in the present (bottom). If the geologic elements—trap, reservoir, charge and seal—are present and the processes occur in the proper order (trap formation followed by hydrocarbon generation, migration and accumulation), a hydrocarbon reservoir may exist. In this case, the reservoir contains gas (red) and oil (green).

To find promising exploration targets, experts deploy various technologies to quantify the likelihood that all these conditions are met. Exploration integrates the efforts of all types of geoscientists—geologists, geophysicists, petrophysicists, paleontologists and geochemists—into a coherent evaluation of how the petroleum systems in a basin have evolved.

The exploration team interprets data from a multitude of physical measurements made at a wide range of scales. Geologists study outcrops to determine the types of rocks that may be present at depth in the basin. They review aerial photography and satellite imagery to find folds, faults and seeps. From well logs, geologists can characterize the nature of subsurface formations and correlate formations from one well to another, creating maps and 3D models of sedimentary basins. Cores, or samples of rocks taken from boreholes, provide ground truth readings on a fine scale.

Geophysicists interpret seismic, magnetic and gravimetric surveys preformed on land and at sea to identify tapping structures and potential hydrocarbon indicators. By correlating seismic data with information from wells, geophysicists can determine the depth of a prospective structure. Petrophysicists analyze well log data to determine the volume and types of sediments and fluids present and the ability of the rock to produce hydrocarbons. Paleontologists examine fossils to assign ages and depositional environments to rock sequences. Geochemists assess the potential of the source rock to generate petroleum.

The results of these studies can be put into computer simulations called petroleum system models that determine potential accumulation locations, volume and content, along with information that will be used to judge their chances of success.

Typically, exploration geologists focus on a particular region to develop a play, or collection of potential petroleum prospects with similar geology. They use the characteristics of previous discoveries to predict the occurrence of similar but undiscovered accumulations. After collecting and interpreting the available data, geologists identity leads, or features of interest, on which to focus additional data-collection and interpretation efforts. Leads that have been investigated and found to be potential traps for hydrocarbons are designated as prospects.

Once the prospects in a region have been identified, exploration experts rank them according to risk and reward. To Optimize their assets, oil and gas exploration and production companies strive to maintain a balanced portfolio of projects with outcomes ranging from high risk, high reward to lower risk and reward.

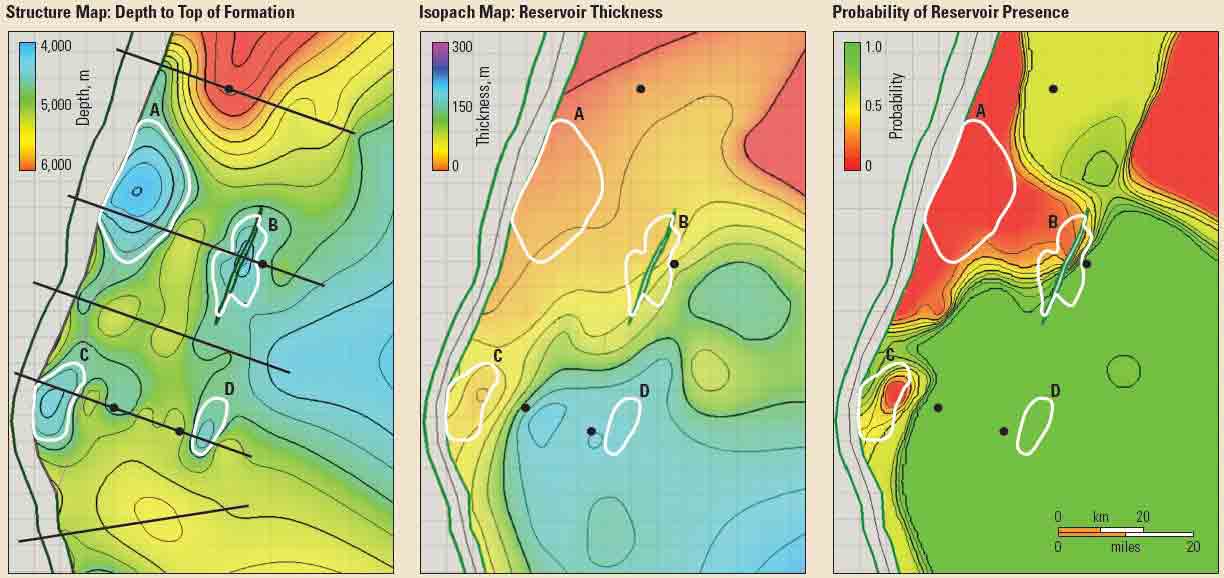

A key challenge is to understand the range of potential outcomes in a prospect, since there are rarely sufficient data for a firm estimate of how much oil or gas might be in an undrilled structure. Geologists calculate a range of volumes of hydrocarbon reserves by combining information on the areal extent and thickness of prospective reservoir rock, the expected porosity of that rock and the types of hydrocarbon present in the trap (Figure 2) . Detailed 3D seismic surveys can provide images of the subsurface to improve these estimates, but only by drilling a well can an exploration company confirm a structure's content.

Some companies have new-venture teams that are always on the lookout for new basins to explore. Exploration teams frequently begin investigating an area once the host country announces an upcoming licensing round. A country offers acreage for lease to exploration companies in return for a fee, royalties and an obligation to perform additional work, such as acquiring seismic data or drilling wells. The company with the highest bid typically wins the right to explore that lease area. Before bidding, exploration teams attempt to evaluate lease offerings using all available data. If the bid is successful, the company commissions further data-collection campaigns. Then the exploration team integrates the new data with their previously gathered information to design a drilling program to test the prospect.

An exploration well drilled in a new area is known as a wildcat. A well that encounters significant amounts of petroleum is a discovery. If it does not encounter commercial quantities of petroleum, it is a dry hole, which is usually plugged and abandoned. Once a discovery has been made, appraisal wells may be drilled to define the extent of the field.

E&P companies are continually testing new ideas in petroleum exploration. Recently, prolific reservoirs have been discovered in deep ocean basins, where water depths exceed 3,000m (10,000 ft). Oil and gas accumulations have been found beneath salt layers hundreds of meters thick. Companies have also discovered they can tap into source rocks to produce oil and gas before these fluids are expelled. The secrets to success in all these exploration endeavors are talented people and advanced technology.

Oilfield Review Spring 2013: 25, no. 1.

Copyright © 2015 Schlumberger.

For help in preparation of this article, thanks to George Waters, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA, and Diego Narvaez, Houston.